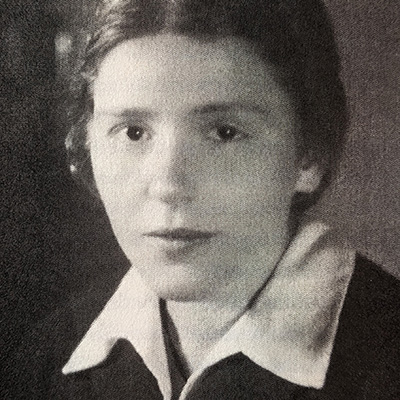

Alumna Elfriede Therese Dubois (BA French Language and Literature, 1943; MA French Language and Literature, 1945) escaped the Nazi annexation of her native Austria to make a new life in Britain. More than 50 years later, her son Dominique wrote a memoir in tribute.

It was only in the last decade of her life that Elfriede Dubois would talk to her son Dominique about the traumatic years where she fled Austria and made a fresh start in the UK amid the backdrop of World War 2.

Forced out of her university studies in Vienna due to her Jewish background after the Nazi occupation, Elfriede arrived in Britain in 1939 with her life in a suitcase.

Forced out of her university studies in Vienna due to her Jewish background after the Nazi occupation, Elfriede arrived in Britain in 1939 with her life in a suitcase.

And while she would become an award-winning student at the University of Birmingham, making a successful career in academia and raising a family in Newcastle, Dominique did not discover how his mother grew up until he began researching his family on the internet.

Dominique said: ‘We only started talking about her childhood in 2004, when my mother was 87 and I was 54. She had not really talked about her background at all until then. I did some research on the internet and stumbled across the fact she was Jewish and entitled to compensation from the Austrian government.

‘I felt, morally, I had to share that with her. Once I mentioned her father’s real name and that my research showed our family was Jewish, the story flowed. We continued to talk about her life growing up until about six months before she died in 2013, at the age of 97.’

Escaping occupation

An outstanding student, Elfriede was in the third year of her four-year degree in French, Latin and Greek at the University of Vienna when she was expelled in 1938 following the Anschluss (annexation) of Austria by Nazi Germany.

While she had converted from Jewish to Roman-Catholic in 1934 (and changed her name from Pollitzer to Pichler), life in Austria had become threatening, so her mother arranged for her to emigrate to Britain on a visa scheme looking to employ trainee nurses.

Despite having no background in nursing, and with very little understanding of English, Elfriede took on the task diligently at Salisbury Hospital. With the help of some Quakers, she was eventually cleared by an internment tribunal to continue living and working in the UK following the declaration of war in September 1939.

She was then able to take up studying French at Birmingham, with its long-standing connections to Quakers meaning she was provided with accommodation and a grant for her degree at the Woodbrook Quaker Study Centre, a college in Selly Oak founded by George Cadbury.

Her aptitude as a student was such that she was awarded a first-class degree, completing a three-year course in two years. A Masters’ degree followed, with Elfriede sharing the prestigious Constance Nadel Medal for the best MA of the year.

Birmingham then offered her a scholarship to begin a PhD in 1947 but, a year in, having only just been granted British citizenship and with no regular income, the offer of an assistant lectureship at the University of Sheffield became the prudent option.

While she went on to have a successful career and happy life in her adopted nation, the mental scars of escaping the Holocaust remained with her for her entire life.

While she went on to have a successful career and happy life in her adopted nation, the mental scars of escaping the Holocaust remained with her for her entire life.

‘She learnt soon after the war that her parents, my grandparents, had died in extermination camps in Poland. She said she never wanted to learn more, which I absolutely respect, and I believe it’s very common for a parent survivor,’ said Dominique.

‘There was trauma and shame. She said to me – while wishing she could shake it off – that she felt like she shouldn’t exist. I wanted to write my memoir both as a tribute to her, but also to preserve the memory of my grandparents.’

A life-changing opportunity

Thankfully Birmingham provided her with happy memories despite the hardships of moving from place to place, doing the washing up at a neighbouring college to earn a few extra pence and milking goats on a farm in the summer break.

Dominique added: ‘While she spent 30 years as a lecturer at Newcastle University, and would meet my father while on a research trip to Paris, Birmingham really provided my mother with a life-changing opportunity.

‘She remained deeply grateful for the opportunity to resume her student studies and take up her subsequent career, which she greatly cherished.’

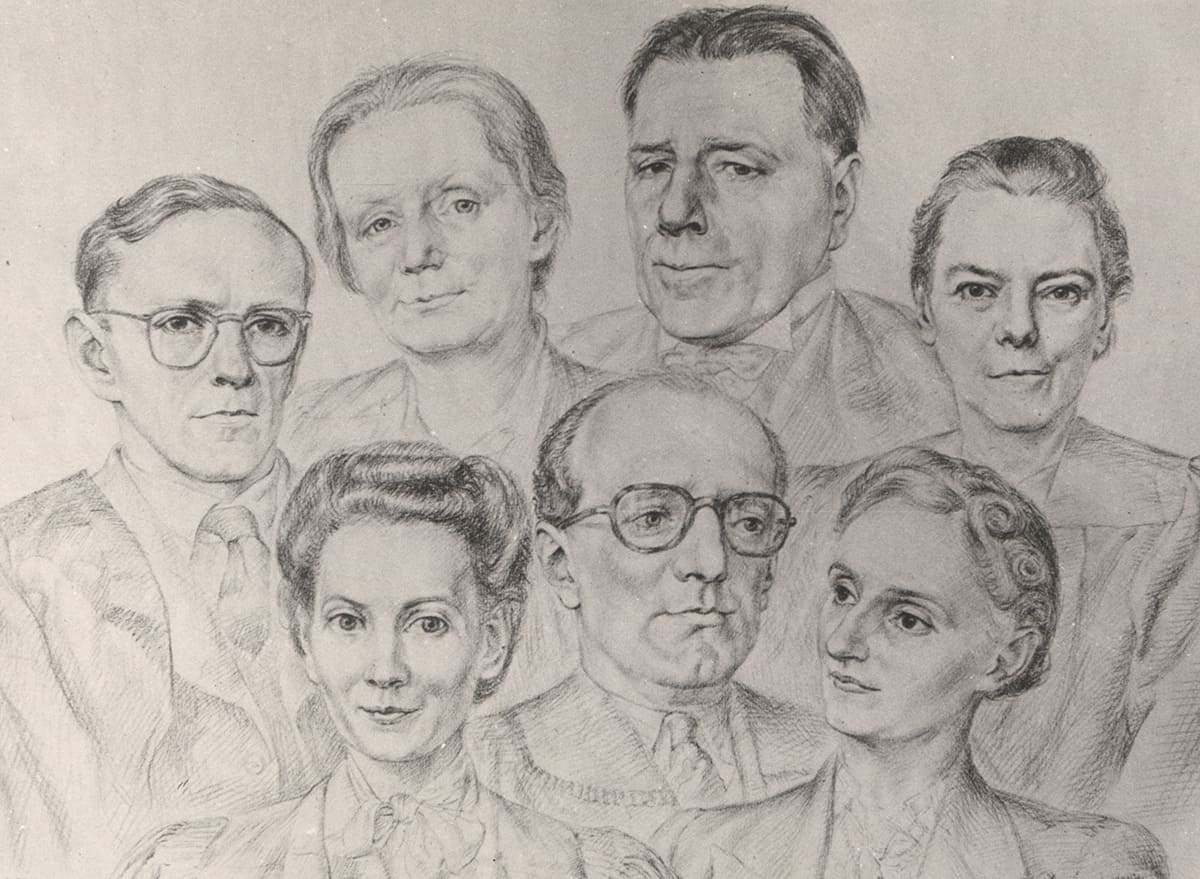

As an example, Dominique has learned that a drawing Elfriede kept for her entire life was of the seven academics who made up the French department during her studies at the University (pictured: UC10/I/3/34 University Archive, Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham).

One of the academics featured was Elfriede’s tutor, Miss Jane Milne, who became a lifelong friend and inspiration. Dominique said: ‘Miss Milne was immensely caring towards my mother. I remember going to Edinburgh as a child to meet her after she retired there.’

Elfriede returned to Birmingham for an alumni reunion of the French Department in May 2000, and Dominique added: ‘By then my mother was 84 and while it had been a long day, she had seen people who she recognised from all those years ago. You could see how much she had enjoyed the opportunity and what the reunion had meant to her.’