In 2009 NASA’s Kepler space telescope was launched to search for Earth-size planets orbiting other stars. Ten years later, the very first potential exoplanet discovered by the mission has now been confirmed as a genuine exoplanet by a team of astronomers, including researchers from Birmingham.

Designed to survey a nearby region of our Galaxy, the Milky Way, Kepler observed 530,506 stars while operating for more than nine years, and has detected more than 2,500 planets.

But confirmation that its very first observed candidate was, in fact, an actual planet (known as Kepler-1658b), would take a decade due to difficulties in assessing the data collected.

Professor Bill Chaplin (BSc Physics, 1990; PhD Physics, 1994; PGCert Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 2001), who leads the Sun, Stars and Exoplanets research at Birmingham, says: ‘Confirming that Kepler’s first exoplanet candidate really is a planet is a wonderful legacy result, which brings things full-circle, now that Kepler has finished taking data.

‘The mission was fantastically successful and found thousands of potential exoplanets; so many, in fact, that it will take many more years to complete a full assessment of the recorded information.’

Staring at the stars

The telescope used the transit method - small dips in brightness as planets cross in front of a star along our line of sight – to reveal ‘planet candidates’, but further analysis is required to confirm them as genuine planets.

Despite being the very first planet candidate discovered by NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope, for much of the time since its signal was discovered it had been marked down as a “false positive” - something in the data masquerading as a real planet. This was in part due to the fact that various properties of the star were off, which made some aspects of the transit signal hard to explain.

Through the use of asteroseismology – the study of stars by observing their resonant oscillations, caused by sound trapped inside the stars – researchers were able to establish that the star was three times larger than previously thought.

This solved the riddle of the unexplained features of the data, and prompted follow-up observations from a ground-based telescope to confirm the exoplanet finding.

The confirmation was led by University of Hawaii graduate student Ashley Chontos, working with the team in Birmingham who played an important role in the asteroseismic analysis.

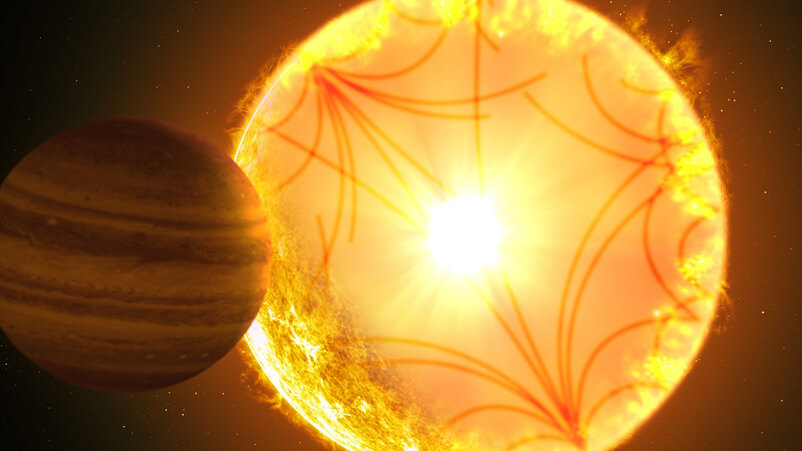

Kepler-1658b is in an extremely close orbit to its host star – orbiting at a distance of only four times the size of the star itself. Standing on the planet, its star would appear 60 times larger than the Sun appears in our sky.

With such a close orbit, the planet will eventually spiral into its host star. The extreme nature of the system has provided new insights on the complex physical interactions between stars and planets.

The sky is a neighbourhood

With Kepler officially retired by NASA in October 2018, scientists are now looking to the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) to continue the search for exoplanets across 85% of the sky – an area 400 times larger than that covered by its predecessor.

Bill adds: ‘When you look up at the night sky, you may wonder how many of the stars you see have orbiting planets. The results from the Kepler mission suggest that each Sun-like star may have at least one.

‘TESS will discover lots of planets orbiting stars close by, and allow us to study them in far greater detail than Kepler’s systems. It is an exciting thought that some of the host stars will be bright enough to observe with the naked eye.’

Hear the latest research findings by following us on social media:

- Follow us on Facebook using @birminghamalum

- Follow us on Twitter using @birminghamalum

- Follow us on Instagram using @birminghamalum

- Join our LinkedIn group