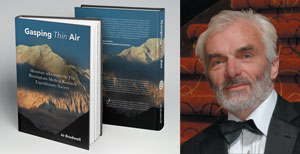

A pioneering society of Birmingham doctors is using their study leave to conquer mountains, where they can make breakthroughs in our understanding of altitude sickness. Founding member Jo Bradwell (MBChB, 1968, DUniv, 2011) has detailed their expeditions in a new book Gasping Thin Air.

A daring society

In 1976, a group of overworked junior doctors in Birmingham's Queen Elizabeth Hospital fantasised about where they would like to trek across the world. In the doctors' mess after long shifts, they formed the Birmingham Medical Research Expeditionary Society (BMRES), and the next year a party of 17 set out for Nepal.

In 1976, a group of overworked junior doctors in Birmingham's Queen Elizabeth Hospital fantasised about where they would like to trek across the world. In the doctors' mess after long shifts, they formed the Birmingham Medical Research Expeditionary Society (BMRES), and the next year a party of 17 set out for Nepal.

This was no ordinary trek. As medics, they wanted to incorporate research directly into their climbs. Every member of the team was a subject in the society's own investigations into altitude sickness, which was poorly understood in the 1970s. Since Nepal, BMRES have travelled to mountains from Argentina to Kenya; anywhere the team could climb quickly enough to produce symptoms of altitude sickness without running serious risks.

Altitude sickness

Altitude sickness happens when the body can't take in enough oxygen. It can result in life-threatening conditions affecting the brain or lungs, and can leave mountain climbers vulnerable at critical moments. Some people suffer terribly with it, while others are unaffected. BMRES research the symptoms and diagnosis of altitude sickness, test drugs for prevention and treatment, experiment with the effect of exercise and much more.

'Rarely has science been so dramatic': The book Gasping Thin Air

As a Professor of Immunology at Birmingham, Jo Bradwell was a founding member of BMRES and its chairman for 35 years. In his book Gasping Thin Air, he brings together 50 years of climbs and research, which saw members of BMRES upside down in a crevasse, facing a killer storm on a mountaintop and camping alongside a glacier.

As a Professor of Immunology at Birmingham, Jo Bradwell was a founding member of BMRES and its chairman for 35 years. In his book Gasping Thin Air, he brings together 50 years of climbs and research, which saw members of BMRES upside down in a crevasse, facing a killer storm on a mountaintop and camping alongside a glacier.

'It is the camaraderie and deep friendship that makes all expeditions special. But the science is our primary motivation. In the 1970s, altitude sickness was a medical mystery waiting to be explored.

'Today, every mountain guidebook includes safe ascent rates, drug doses and the cost of helicopter rescues. Yet there is still much still to discover. How does cognitive impairment affect decision making on the mountains, would more medical first aid posts help, what are the optimal doses for treating altitude sickness and what effect does withdrawal have afterwards? The next generation of BMRES may overleap the achievements of its predecessors.'

The latest climb; the Fellowship of Sikkim

PhD student Kelsey Joyce (front row, centre) joined BMRES in 2019 to help gather data from every climber, which will help the society understand altitude sickness.

PhD student Kelsey Joyce (front row, centre) joined BMRES in 2019 to help gather data from every climber, which will help the society understand altitude sickness.

'My first climb with BMRES took us to the world's third highest mountain; Kanchenjunga in Sikkim, which is part of the Himalayas. The three-week trek began with the worst weather of any BMRES trek; we huddled in wet tents and monsoon lightning blew many of our laptop batteries. But there were many wonderful moments too, from a cricket match with the Sherpas, to eating lunch gazing into the Zema mountain glacier.

'I helped collect as much data as possible from everyone, which gives the members of the team who are doctors more capacity to support anyone feeling ill. We took blood and urine samples from everyone daily, and measured oxygen levels in our blood using pulse oximeters that clip onto your wrist and finger.

'If we can use these fingertip monitors to predict who will get ill, we can take preventative measures. In the mountains, this could help reduce the number of medical emergencies faced by climbers. Once we can all travel again, we're expecting a rush of people travelling on planes and travelling on adventurous trips, where they might experience altitude sickness for the first time. And this research could help people in hospitals; lots of diseases mean people can’t get enough oxygen (including COVID-19).'

Read more about BMRES's trek to Kanchenjunga in chapter 15 of Gasping Thin Air, available from their website.