Staff at the University of Birmingham are leading the way in developing a new and potentially more effective range of treatments to fight cancer.

'Exploiting the body's own immune system to target a tumour is a vastly different approach to conventional treatments and the exciting thing is it has turned from an intellectual pipedream to a therapeutic pipeline.'

Patients diagnosed with colorectal and lung cancer could soon have access to a pioneering new set of treatments that utilise their own immune system to fight tumours.

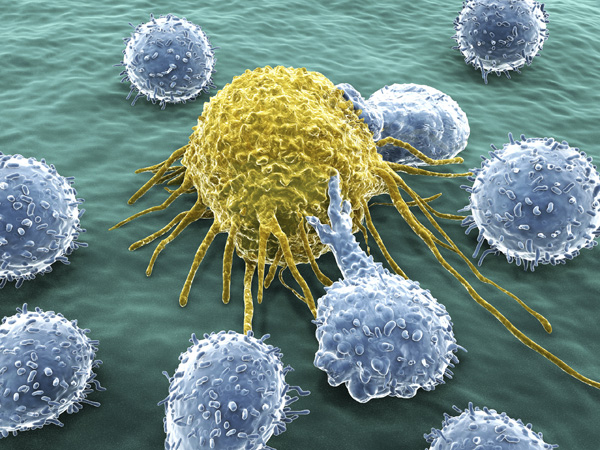

A team of scientists at the University led by Ben Willcox, Professor of Molecular Immunology and Director of the University's Cancer Immunology and Immunotherapy Centre (CIIC), is researching how to unlock the immune system's own natural defences to kill cancer cells.

Clinical trials for skin cancer have already seen some spectacular successes where conventional treatments have failed. Results suggest immunotherapy can provide more effective and long-lasting results on other cancers – exciting new breakthroughs in the battle with the disease.

Ben says: 'The idea of using the immune system to fight cancer is not new, but now years of fundamental research into how the immune system works has allowed the medical community to translate that knowledge into therapies that fully exploit its power.

'They have produced clinical trial results that make cancer immunology one of the most exciting, fast-moving areas in the whole of medicine.'

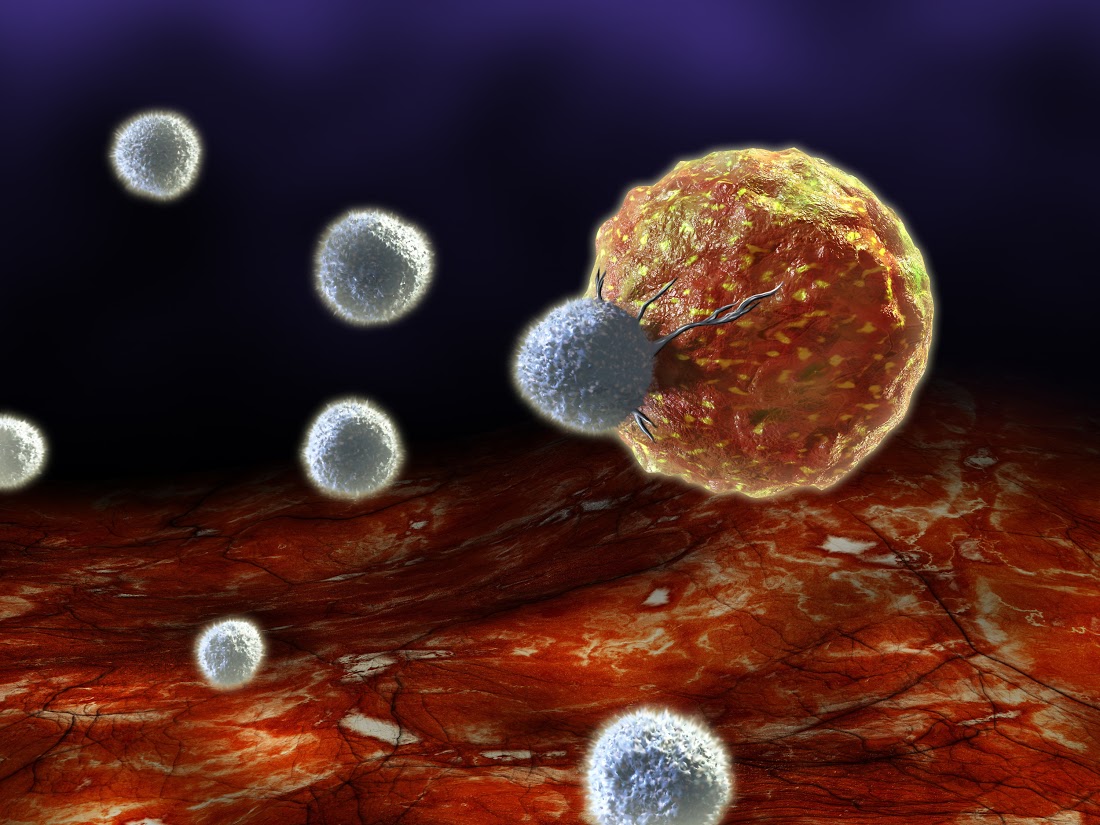

'Our immune system is trained to identify, attack, and destroy foreign cells and ignore our own cells. Cancer cells are able to escape identification or attack in a number of ways, and the medical community has been attempting to overcome this obstacle for years.'

Unlocking the immune system

The immune system provides the body's defence against infection and illness caused by "foreign" invaders. A first line of defence is provided by the skin and stomach acid, but when bacteria, viruses and parasites get past this initial wall, white blood cells work to identify and destroy them.

Vaccinations have demonstrated how the immune system can successfully be manipulated to beat infectious diseases – for example, with the eradication of smallpox. Exploiting our immune system to successfully tackle cancer has, however, left scientists and clinicians stumped for decades.

'Our immune system is trained to identify, attack, and destroy foreign cells and ignore our own cells. This makes cancer cells inherently more camouflaged than foreign invaders,' explains Ben. 'However, even when cancer cells can be recognised, they are able to escape identification or attack in a number of ways, and the medical community has been attempting to overcome this obstacle for years.'

Tumours can either fool white blood cells into ignoring them, hide from detection altogether or force the white blood cells to stop taking action, by making them "put the brakes" on the process of identifying and killing the rogue cells.

But a greater understanding of how these processes take place has given the field of immunotherapy the necessary tools to move from theory to reality.

'Cancer immunotherapy has been heralded as a real turning point in the fight against the disease,' Ben adds. 'In Birmingham, the CIIC group is poised to make a really significant contribution to this area going forward.'

The power of the CIIC

CIIC is a collaborative grouping of scientists and clinicians specifically working together to harness the power of the immune system to treat cancer by researching and testing new immunotherapy treatments.

CIIC is a collaborative grouping of scientists and clinicians specifically working together to harness the power of the immune system to treat cancer by researching and testing new immunotherapy treatments.

Based in Birmingham, the research the CIIC carries out is wide-ranging. As Ben explains: 'Part of the team is working to define which components of tumours distinguish them from normal tissues, and which of these are likely to make good targets, as well as studying the microenvironment within tumours.

'In addition, groups within the CIIC are exploring new immunotherapeutic methods, including expanding powerful antibody-based strategies to more patients, optimising cellular therapies for challenging cancers, and novel vaccination approaches.

'These are focused on key disease settings, including blood cancers, but also a range of solid tumours including colorectal cancer, lung cancer, head and neck cancer, and liver cancer.

'This is where the clinicians within the grouping, and their associated clinical teams, have a really crucial role to play.

'The potential of these treatments is massive – transformational stuff, it puts the hairs on the back of the neck up to think you've not done anything besides give something to activate a patient's own immune cells.'

Hair-raising results

Leading the clinical work is Gary Middleton, Professor of Medical Oncology at the University and Clinical Director of CIIC, who works at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham treating patients with a range of cancers.

He has a particular interest in lung and colorectal cancer, as they appear to be particularly responsive to immunotherapy. His work is now focused on understanding how to stimulate anti-tumour immune responses and develop more effective, personalised treatments.

Gary says: 'The discovery in 2012 that antibodies could take the brakes off a patient's own immune cells and activate the body's defences was tremendously exciting, both for the development of a new treatment for patients but also for showing that the immune system can in fact successfully kill cancer cells.

'We started our own trials in 2013 and the results have been unbelievable. I have seen dramatic responses to immunotherapy drugs in my own patients, including those who have failed on conventional anti-cancer therapies; some of these responses might even represent cures.

'The potential of these treatments is massive – transformational stuff, it puts the hairs on the back of the neck up to think you've not done anything besides give something to activate a patient’s own immune cells.'

While CIIC's work has seen positive results against certain types of cancer, the hope remains that immunotherapy could also be successful for a wider range of patients. Further research will be required to unlock the full potential of these treatments and the University is uniquely placed to do so as part of Birmingham Health Partners, a strategic alliance with Birmingham Children's Hospital and University Hospitals Birmingham.

CIIC is linked to the Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, conveniently located next to the University campus, which is also host to the Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit, one of the largest cancer clinical trial units in Europe. Their work is supported by the Institute of Translational Medicine (ITM), which opened on campus in 2015 with the objective of accelerating medical research findings from the laboratory bench to patients.

With the research and clinical facilities so close together, patients can be co-located alongside clinicians and researchers, accelerating the development of new immunotherapies to fight cancer.

With the research and clinical facilities so close together, patients can be co-located alongside clinicians and researchers, accelerating the development of new immunotherapies to fight cancer.

Ben adds: 'So far it appears that when a tumour is significantly different genetically to our normal cells, we have a good chance of unleashing a strong immune attack against it. However, when this is not the case, our immune system is much more reluctant to kick in. Finding novel ways to tackle that problem is a high priority and should extend the reach of these therapies.

'Exploiting the body's own immune system to target a tumour is a vastly different approach to conventional treatments and the exciting thing is it has turned from an intellectual pipedream to a therapeutic pipeline.'